Hurricanes

Nature’s tropical fury spells trouble for aviation.

By Karsten Shein

Com-Inst. Climate Scientist

From flash flooding and landslides in North Carolina to tornadoes across central Florida, nature has demonstrated the wide-ranging nature of its potential.

The 2024 Atlantic Hurricane season, which left hundreds dead or missing and devastated the southern Appalachians with catastrophic destruction, has been by most measures an “average” season, yet at the same time, it may be a herald our not-too-distant future.

In any given year, around 86 tropical cyclones form around the world. Of those, roughly 47 of those attain hurricane strength.

Every tropical ocean basin has generated tropical cyclones, although the tropical South Atlantic has only had a few tropical cyclones and only one recorded hurricane due to generally unfavorable formative conditions.

Regardless of ocean basin, tropical cyclones form between about 5° and 23.5° latitude on either side of the equator due to the need for sufficient Coriolis Effect – which is zero at the equator – to ensure storm rotation.

The other necessary formative factors are warm sea surface temperatures, over 81° F (27° C), high humidity from the surface to at least 500 mb (FL200 in the tropics), and low windshear and high instability throughout the troposphere.

Lastly, hurricane formation also needs a disturbance, usually in the form of a wave in one of the low-level easterly jet streams that form throughout the tropics around the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), migrating north or south as it follows the seasonal sun. However, even if all of the conditions are met, a cluster of thunderstorms may not organize into a tropical cyclone because even small variations in atmospheric structure can prevent the system from becoming self-sustaining.

Hurricane season depends on ocean basin, but in most places conditions are met only during the warm months. For the northern hemisphere, the season goes from around June to November. In the southern hemisphere, it’s from December through May.

However, as sea surface temperatures continue to rise worldwide, tropical cyclones (some strong) have formed outside these windows. Statistically, tropical cyclone danger peaks in June in the Indian Ocean. Peak season for the Atlantic, Caribbean, and North Pacific is September. In the South Pacific and southern Indian Ocean, it’s in February. All pilots should familiarize themselves with tropical cyclone season in the regions they fly.

Forecasting

What makes tropical cyclones dangerous is their ability to strengthen as they evolve. These systems are basically heat pumps, so as long as the formative conditions remain (warm ocean, high humidity, instability, and low windshear) the system can continue to grow.

Meteorologists use atmospheric observations taken from satellite and aircraft to monitor conditions and are able to forecast a cyclone’s strength and ability to sustain its organization with relatively good accuracy.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the cyclone’s path. While a cyclone is steered generally by surrounding weather patterns, such as large pressure systems, the exact path and speed it takes are dictated by many complex ocean-atmosphere interactions at various scales.

This is why as forecast lead time grows, so does the uncertainty about the cyclone’s path, and why forecasters will show a “cone of uncertainty” around the most likely track.

The forecast track is derived from a suite of weather and hurricane-specific forecast models. The closer the model tracks agree, the more confidence forecasters have in the likely track. For example, in October 2024, Hurricane Milton exhibited strong model agreement, and the track forecast 4–5 days ahead of landfall was off by just about 12 miles. The cone itself is based on average forecast error over the past several years, but as the models evolve, it is likely that the cone will shrink.

While stronger storms are normally more dangerous than weaker ones, all tropical cyclones present a danger to aviation. Some of the greatest storm rainfall totals have come from stalled tropical cyclones, while some major hurricanes have passed through an area with only minimal damage.

But even a tropical storm (34- to 63-kt winds) is capable of moving or flipping a poorly secured aircraft or damaging it with flying debris, or flooding an airport or approach roads with prolonged rainfall. Further, a tropical storm can be larger than a major hurricane, and may affect areas further from its center. Compact storms can be less than 50 mi (80 km) diameter to over 1000 mi (1600 km) – measured by the radius of storm force winds.

Because tropical cyclones are easily monitored by satellite and forecast with relative accuracy, the greatest danger to aviation is to airports, aircraft, pilots, airport staff, and others on the ground in the storm’s path.

While strong and gusty winds from a tropical cyclone will mobilize debris that can damage aircraft, ground vehicles, hangars, and other structures, a great deal of wind damage is from the many tornadoes produced by the thunderstorms in the rain bands. Hurricane Ivan (2004), for example, created 120 tornadoes.

Airports near the coastline are also susceptible to storm surge. As the storm moves ashore, winds are also pushing water with it that will inundate low-lying coastal land. Even far from the storm, surge may raise water levels by 2–3 ft (1 m). Near the storm’s center, however, this surge can easily exceed 10 ft (3 m) and the surge will continue to be propelled inland by the winds until the storm passes.

Unfortunately, because intense storms occasionally strike densely populated regions that have minimal safety measures in place, storm surge contributes to around 90% of storm-related fatalities. For example, surge from a cyclone that hit Bangladesh in 1970 took the lives of at least 300,000 people. Many who died during Hurricane Katrina (2005) were trapped in their homes as the storm surge breached numerous levees around New Orleans.

Even airports and communities far inland are often devastated by tropical cyclones. Although they may lose much of their energy once their supply of warm ocean water is cut off, they are still capable of producing high winds and heavy rain.

The September 2024 disaster in southern Appalachia from then tropical storm Helene was primarily due to heavy rain falling on already saturated ground, resulting in flash flooding and landslides. Rainfall was enhanced by the mountains helping lift the humid tropical air.

Planning

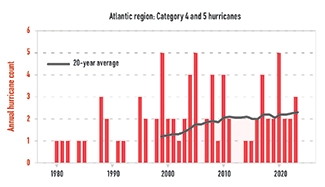

Unfortunately, as we move into a hotter future, we are already seeing that more tropical cyclones are intensifying into major hurricanes – double the number of category 3 and up since 2000. And we can expect that trend to continue.

Warmer air and water means more fuel for hurricanes, translating into higher winds and more rain. Tropical cyclones are also projected to slow down, suggesting that storms may take longer to pass over an area.

Any pilot living in an area that may be affected by a tropical cyclone should have a plan in place to remain safe, and, if feasible, evacuate their aircraft out of harm’s way. Fortunately, given the high potential loss, many insurance companies will reimburse aircraft relocation costs and may even send a ferry pilot to evacuate your aircraft so you can focus on your own safety. If this service is not available, pilots may make standing arrangements with FBOs at inland airports to accommodate their aircraft, and some may elect to always park with enough fuel aboard through hurricane season to be able to evacuate at a moment’s notice.

Finally, if your plan includes aircraft evacuation, be sure to do so well before the storm. Many airports will close a day or 2 before a strike to prepare. Whatever plan a pilot, crew or flight department settles on, practicing it before the season starts can be a wise idea to fine tune it and avoid problems if a storm approaches.

Karsten Shein is cofounder of 2DegreesC.org. He was director of the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at the University of Illinois, and a NOAA and NASA climatologist. Shein holds a comm-inst pilot license.

Karsten Shein is cofounder of 2DegreesC.org. He was director of the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at the University of Illinois, and a NOAA and NASA climatologist. Shein holds a comm-inst pilot license.